9 Linux Administration

You’re accustomed to interacting with a computer and phone running MacOS, Windows, iOS, or Android. But, most servers don’t run any of those.

Linux is the world’s predominant operating system (OS) outside of personal computers and phones. Almost all of the world’s embedded computers run Linux – in ATMs, cars, planes, TVs, smart thermostats, and most other gadgets and gizmos. Android is a version of Linux, as is ChromeOS. Almost all of the world’s supercomputers run Linux.

Most importantly for our purposes, most of the world’s servers run on Linux.1

To administer a server, you’ll have to learn a little about Linux. In this chapter, you’ll learn about the history of Linux and how to navigate and manipulate a server running Linux. Many of these techniques are also useful on your laptop’s command line.

A brief history of Linux

A computer’s OS defines how applications can interact with the underlying hardware. The OS dictates how files are stored and accessed, how applications are installed, how network connections work, and more.

Before the early 1970s, the computer hardware and software market looked nothing like today. Computers of that era had extremely tight linkages between hardware and software. There was no Microsoft Word you could use on a machine from Dell, HP, or Apple.

Instead, every hardware company was also a software company. If Example Corp’s computer did text editing, it was because Example Corp had written (or commissioned) text editing software specifically for their machine. If Example Corp’s machine could run a game, Example Corp had written that game just for their computer.

Then, in the early 1970s, researchers funded by AT&T’s Bell Labs released Unix – the first operating system. Now, there was a piece of middleware that reduced the need for coordination between computer manufacturers and software developers. Computer manufacturers could design computers that ran Unix, and developers could write software that ran on Unix.

The one issue (for everyone but Bell Labs) was that they were paying Bell Labs a lot of money for Unix licenses. So, in the 1980s, programmers started writing Unix-like OSs. These so-called Unix clones behaved like Unix but didn’t include any actual Unix code.2

In 1991, Linus Torvalds – then a 21-year-old Finnish grad student – released an open-source Unix clone called Linux via a nonchalant newsgroup posting, saying, “I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu)…Any suggestions are welcome, but I won’t promise I’ll implement them :-).”3

The Linux project outgrew that modest newsgroup post. There are over 600 distros (short for distributions) of Linux, which differ by technical attributes and licensing model. The number of distros reflects the natural fragmentation of popular open-source projects and the disparate requirements for systems as varied as your car’s infotainment system, a smartphone, and the controller for your smart thermostat.

Luckily, you don’t have to know hundreds of distros. Most organizations use one of only a handful on their servers. The most common open-source distros are Ubuntu or CentOS. Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) is the most common paid distro.4 Many organizations on AWS are using Amazon Linux, which is independently maintained by Amazon but was originally a RHEL derivative.5

Most people, including me, prefer Ubuntu when they have a choice. It’s a little simpler and easier to configure than the others.

Ubuntu versions are numbered by the year and month they were released. Most people use the Long Term Support (LTS) releases, released in April of even years.

Ubuntu versions have fun alliterative names, so you’ll hear people refer to releases by name or version. As of this writing, most Ubuntu machines run Focal (20.04, Focal Fossa), Jammy (22.04, Jammy Jellyfish), or Noble (24.04, Noble Numbat).

Administering Linux with bash

Linux is administered from the command line using bash or a bash alternative like zsh. The philosophy behind bash and its derivatives says that you should be able to accomplish anything you want with small programs invoked via a command. Each command should do just one thing, and complicated things should be performed by composing commands – taking the output from one as the input to the next.

Invoking a command is done by typing the command on the command line and hitting enter. If you ever find yourself stuck in a situation you can’t seem to exit, ctrl + c will quit in most cases.

Helpfully, most bash commands are an abbreviation of the word for what the command does. Unhelpfully, the letters often seem somewhat random.

For example, the command to list the contents of a directory is ls, which mostly makes sense. Over time, you’ll get very comfortable with the commands you use frequently.

Bash commands can be modified to behave the way you need them to.

Command arguments provide details to the command. They come after the command with a space in between. For example, if I want to run ls on the directory /home/alex, I can run ls /home/alex on the command line.

Some commands have default arguments. For example, the default argument for the ls command is the current directory. So if I’m in /home/alex, I’d get the same thing from either ls or ls /home/alex.

Options or flags modify the command’s operation and come between the command and arguments. Flags are denoted by having one or more dashes before them. For example, ls allows the -l flag, which displays the output as a list. So, ls -l /home/alex would get the files in /home/alex as a list.

Some flags themselves have flag arguments. For example, the -D flag allows you to specify how the datetime from ls -l is displayed. So running ls -l -D %Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S /home/alex lists all the files in /home/alex with the date-time of the last update formatted in ISO-8601 format, which is always the correct format for dates.

Bash commands are always formatted as <command> <flags + flag args> <command args>.

It’s nice that this structure is standard. It’s not nice that the main argument is at the end because it makes long bash commands hard to read. To make commands more readable, you can break the command over multiple lines and include one flag or argument per line. You can tell bash you want it to continue a command after a line break by ending the line with a space and a \.

For example, here’s that long ls command more nicely formatted:

Terminal

> ls -l \

-D %Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S \

/home/alexAll flags and command arguments are found on the program’s man page (short for manual). You can access the man page for any command with man <command>. You can scroll the man page with arrow keys and exit with q.

Bash is a fully functional programming language, so that you can assign variables with <var-name>=<value> (no spaces allowed) and access them $<var-name>. The bash version of print is echo.

For example, a classic “Hello World!” in bash looks like:

Terminal

> MSG="Hello World!"

> echo $MSG

Hello World!For the most part, you’ll write commands directly on the command line. You also can write and run bash scripts that include conditionals, loops, and functions. Bash scripts usually end in .sh and are often run with the sh command like sh my-script.sh.

The advantage of writing bash scripts is that they can run basically anywhere. The disadvantage of writing bash scripts is that bash is a truly ugly programming language that is hard to debug.

Programs run on behalf of users

Whenever a program is running, it is running as a particular user identified by their username.

On any Unix-like system, the whoami command returns the username of the active user. For example, running whoami might look like:

Terminal

> whoami

alexkgoldUsernames have to be unique on the system – but they’re not the true identifier for a user. A user is uniquely identified by their user ID (uid), which maps to all the other user attributes like username, password, home directory, groups, and more. The uid for a user is assigned when the user is created and usually doesn’t need to be changed or specified manually.6

Each human who accesses a Linux server should have their own account. In addition, many applications create service account users for themselves and run as those users. For example, installing RStudio Server will create a user with username rstudio-server. Then, when RStudio Server goes to do something – start an R session, for example – it will do so as rstudio-server.

User uids start at 10,000 with those below 10,000 reserved for system processes. There’s also one special user – the admin, root, sudo, or superuser who gets the special uid 0.

Users belong to groups, which are collections of one or more users. Each user has exactly one primary group and can be a member of secondary groups. By default, each user’s primary group is the same as their username.

Like a user has a uid, a group has a gid. User gids start at 100.

The id command shows a user’s username, uid, groups, and gid. For example, I might be a member of several groups, with the primary group staff.

Terminal

> id

uid=501(alexkgold) gid=20(staff) groups=20(staff),

12(everyone), ...If you ever need to add users to a server, the easiest way is with the useradd command. Once you have a user, you may need to change the password, which you can do at any time with the passwd command. Both useradd and passwd start interactive prompts, so you don’t need to do more than run those commands.

If you ever need to alter a user – the most common task is adding a user to a group – you would use the usermod command with the -aG flag.

Permissions dictate what users can do

In Linux, everything you can interact with is just a file. Every log – file. Every picture – file. Every application – file. Every configuration – file.

So whether a user can take an action is determined by whether they have the proper permissions on a particular file.

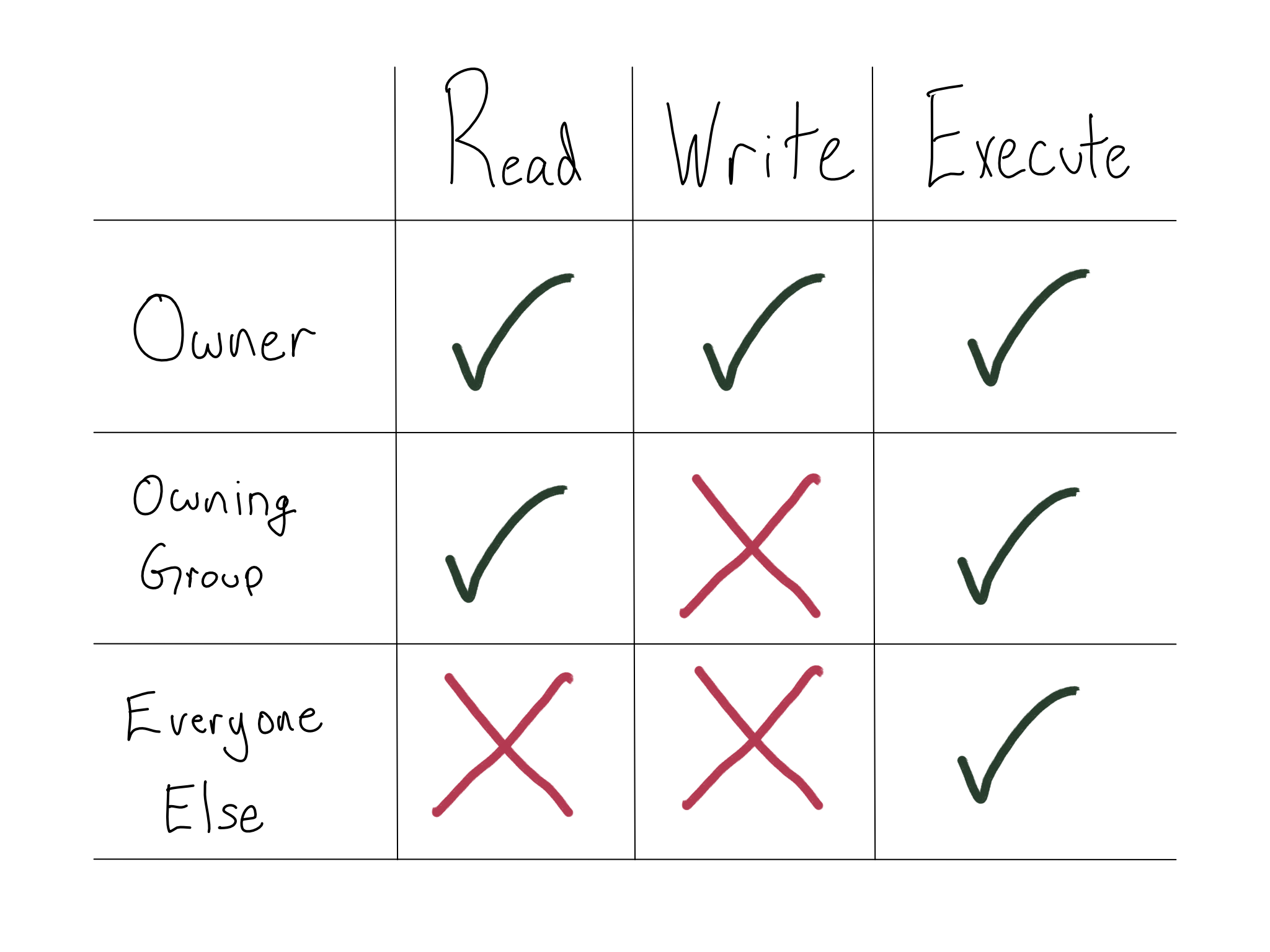

Basic Linux permissions (POSIX permissions) consist of a \(3*3\) matrix of read, write, and execute for the owner, owning group, and everyone else. Read means the user can see the contents of a file, write means the user can save a changed version, and execute means they can run the file as a program.

There are more complex ways to manage Linux permissions. For example, you might hear about Access Control Lists (ACLs). They’re beyond the scope of this book.

There is more information on how organizations manage users and what they can do in Chapter 16, which is all about auth.

For example, here’s a set of permissions that you might have for a program that you want anyone to be able to run, group members to inspect, and only the owner to change.

Directories also have permissions – read allows the user to see what’s in the directory, write allows the user to alter what’s in the directory, and execute allows the user to enter the directory.

File permissions and directory permissions don’t have to match. For example, a user could have read permissions on a directory to see the names of the files, but not have read permissions on any of the files so they can’t look at the contents.

When you’re working on the command line, you don’t get a little grid of permissions. Instead, they’re expressed in one of two ways. The first is the string representation, a 10-character string that looks like -rw-r–r--.

The first character indicates the type of file: most often - for normal (file) or d for a directory.

The following nine characters indicate the three permissions for the user, the group, and everyone else. There will be an r for read, a w for write, and an x for execute or - to indicate that they don’t have the permission.

So the permissions in the graphic would be -rwxr-x--x for a file and drwxr-x--x for a directory.

The best way to get these permissions is to run the ls -l command. For example:

Terminal

> ls -l

-rw-r--r-- 1 alexkgold staff 28 Oct 30 11:05 config.py

-rw-r--r-- 1 alexkgold staff 2330 May 8 2017 credentials.json

-rw-r--r-- 1 alexkgold staff 1083 May 8 2017 main.py

drwxr-xr-x 33 alexkgold staff 1056 May 24 13:08 testsEach line starts with the string representation of the permissions followed by the owner and group so you can easily understand who should be able to access that file or directory.

All of the files in this directory are owned by alexkgold. Only the owner (alexkgold) has write permission, but everyone has read permission. In addition, there’s a tests directory, with read and execute for everyone and write only for alexkgold.

You will probably need to change a file’s permissions when administering a server. You can do so using the chmod command.

For chmod, permissions are indicated as a three-digit number, like 600, where the first digit is the permission for the user, the second for the group, and the third for everyone else. To get the right number, you sum the permissions as follows: 4 for read, 2 for write, and 1 for execute. You can check for yourself that any set of permissions is uniquely identified by a number between 1 and 7.7

So to implement the permissions from the graphic, you’d want the permission set 751 to give the user full permissions (4 + 2 + 1), read and execute (4 + 1) to the group, and execute only (1) to everyone else.

If you spend any time administering a Linux server, you will almost certainly find yourself applying chmod 777 to a directory or file to rule out a permissions issue.

I can’t tell you not to do this – we’ve all been there. But, if it’s something important, change it back once you’ve figured things out.

You might want to change a file’s owner or group. You can change users and groups with the chown command. Users get changed with a username, and groups can be changed with the group name prefixed by a colon.

Sometimes, you might not be the correct user to take a particular action. If you want to change your user, you can use the su (switch user) command. You’ll be prompted for a password to make sure you’re allowed.

The admin or root user has full permissions on every file, and there are some actions that only the root user can do. When you need to do root-only things, you usually don’t want to su to switch to be the root user. It’s too powerful. And, if you have user-level configuration, it all gets left behind.

Instead, individual users can be granted the power to temporarily assume root privileges without changing to be the root user. This is accomplished by making them members of the admin group. If a user is a member of the admin group, they can prefix commands with sudo to run those commands with root privileges.

The name of the admin group varies by distro. In Ubuntu, the group is called sudo.

The Linux filesystem is a tree

All the information available to a computer is indexed by its filesystem, which comprises directories or folders, which are containers for other directories and files.

You’re probably used to browsing the filesystem with your mouse on your laptop. Apps completely obscure the filesystem on your phone, but it’s there. On a Linux server, the only way to traverse the filesystem is with written commands. Therefore, a good mental model for the filesystem on your server is critical.

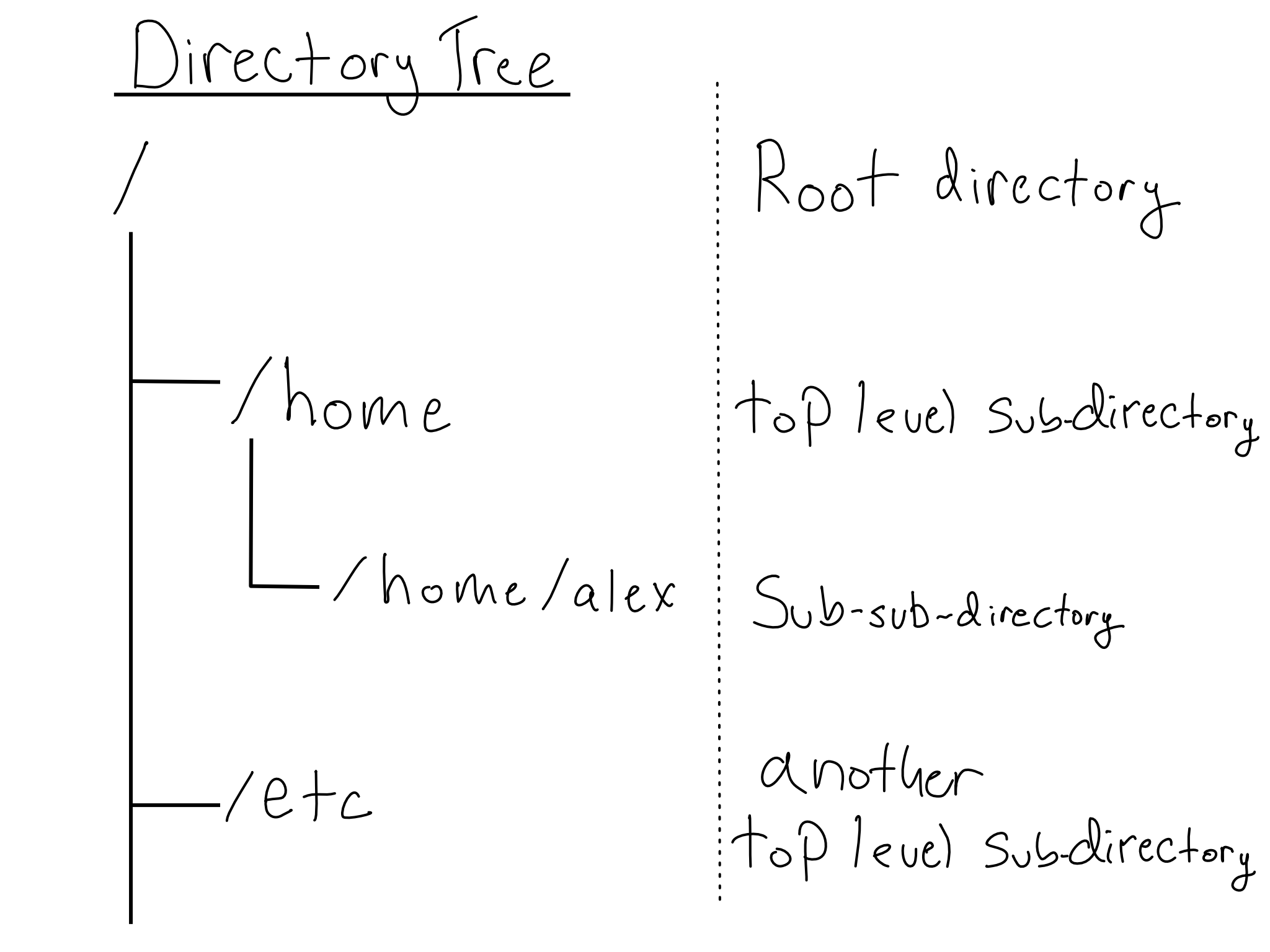

In Linux, each computer has precisely one filesystem, based at the root directory, /. The rest of the filesystem is a tree (or perhaps an upside-down tree). Every directory is contained in by a parent directory and may contain one or more children or sub-directories.8 A / in between two directories means that it’s a sub-directory.

Every directory is a sub-directory of / or a sub-directory of a sub-directory of / or…you get the picture. The /home/alex file path defines a particular location, the alex sub-directory of /home, itself a sub-directory of the root directory, /.

It’s never necessary, but viewing the tree-like layout for a directory can sometimes be helpful. The tree utility can show you one. It doesn’t always come pre-installed, so you might have to install it.

Because the entire Linux filesystem is based at /, it doesn’t matter what physical or virtual disks you have attached to your system. They will fall somewhere under the main filesystem (often inside /mnt), but the fact that they’re on separate drives is obscured from the user.

This will be familiar to MacOS users because MacOS is based on an operating system called BSD that, like Linux, is a Unix clone. If you’re familiar with Windows, the Linux filesystem may seem strange.

In Windows, each physical or logical disk has its own filesystem with its own root. You’re probably familiar with C: as your main filesystem. Your machine may also have a D: drive. If you’ve got network share drives, they’re likely at M: or N: or P:.

Another difference is that Windows uses \ to separate file path elements rather than /. This used to be a big deal, but newer versions of Windows accept file paths using /.

Working with File Paths

Whenever a program runs, it runs at a particular path in the filesystem called the working directory. You can get the absolute path to your working directory with the pwd command, an abbreviation for print working directory.

When you want a program to run the same regardless of where it’s run from, it’s best to use an absolute path, specified relative to the root. Absolute paths are easy to recognize because they start with /.

Sometimes, it’s convenient to use a relative file path, which starts at the working directory, denoted by .. For example, if I want to access the data subdirectory of the working directory, that would be available at ./data.

The working directory’s parent is at ... You could see everything in the parent directory of your current working directory with ls .. or its parent with ls ../...

All accounts representing actual humans should have a home directory, which usually live inside /home.

The home directory and all its contents are owned by the user to whom it belongs. The home directory is the user’s space to store what they need, including user-specific configuration. Users can find their home directory at ~.

You will need to change your working directory, which you can do with the cd command, short for change directory. You can use either absolute or relative file paths with cd. If you were in /home/alex and wanted to navigate to /home, either cd .. or cd /home would work.

Some files or directories are hidden so they don’t appear in a normal ls. You know a file or directory is hidden because its name starts with .. Hidden files are usually configuration files you don’t manipulate in normal usage. These aren’t secret or protected in any way; they’re just skipped by ls for convenience. If you want to display all files in a directory, including hidden ones, you can use the -a flag (for all) with ls.

You’ve already seen a couple of hidden files in this book – like the .github directory, command line configuration in .zprezto and .zshrc, and Python environmental configuration in .env. You might also be familiar with .gitignore, .Rprofile, and .Renviron.

Moving files and directories

You will frequently need to change where files and directories are on your system, including copying, deleting, moving, and more.

You can copy a file or directory from one place to another using the cp command. cp leaves the old file or directory behind and duplicates it at the specified location. You can use the -r flag to copy everything in a directory recursively.

You can move a file with the mv command, which does not leave the old file behind. If you want to remove a file entirely, you can use the rm command. The -r (recursive) flag can be used with rm to remove everything within a directory and the -f (force) flag can skip rm double-checking you really want to do this.

Be very careful with the rm command, especially with -rf.

There’s no recycle bin. Things that are deleted are instantly deleted forever.

If you want to make a directory, mkdir makes a file path. It can be used with relative or absolute file paths and can include multiple sub-directories. For example, if you’re in /home/alex, you could mkdir project1/data to make a project1 directory and data sub-directory.

The mkdir command throws an error if you try to create a path that includes some existing directories – for example, if project1 already existed in the example above. The -p flag can be handy to create only the parts of the path that don’t exist.

Sometimes, it’s useful to operate on every file inside a directory. You can get every file that matches a pattern with the wildcard, *. You can also do partial matching with the wildcard to get all the files that match part of a pattern.

For example, let’s say I have a /data directory and want to put a copy of only the .csv files inside into a new data-copy sub-directory. I could do the following:

Terminal

> mkdir -p /data/data-copy

> cp /data/*.csv /data/data-copyMoving Things to and from the Server

It’s very common to have a file on your server that you want to move to your desktop or vice versa. There are a few different ways to transfer files and directories.

If you’re moving multiple files, first combining them into a single object can make things easier. The tar command turns a set of files or a whole directory into a single archive file, usually with the file suffix .tar.gz. Creating an archive also does some compression. The amount depends on the content.

In my opinion, tar is a rare failure of bash to provide standalone commands for anything you need to do. tar is used to create and unpack (extract) archive files. Telling it which one requires several flags. You’ll basically never use tar without a bunch of flags, and the incantation is hard to remember. I google it every time I use it. The flags you’ll most often use are in the cheat sheet in Appendix D.

You can move files to or from a server with the scp command. scp (short for secure copy) is cp, but with an SSH connection in the middle.9

Since scp establishes an SSH connection, you need to make the request to somewhere that is accepting SSH connections. That means that whether you’re copying something to or from a server, you’ll run scp from a regular terminal on your laptop, not one already SSH-ed into your server.

Regular ssh options work with scp, like -i and -v.

Pipes and redirection

You can always copy and paste command outputs or write them to a file, but it can also be helpful to just chain a few commands together. Linux provides a few handy operators that you can use to make this easy.

The simplest operator is the pipe |, which takes the output of one command and makes it the input for the subsequent command.

For example, you might want to see how many files are in a directory. The wc -l (word count, lines) command counts lines, so you could do ls | wc -l since each file returned by ls is counted as a line.

The R pipe, %>%, operates very much like the Linux pipe. It was first introduced in the {magrittr} package in 2013 and is a popular part of the {tidyverse}.10

The {magrittr} pipe was itself inspired by pipe operators from Unix (Linux) and the F# programming language.

Due to its popularity, the pipe |> was formally added to the base R language in R 4.1 in 2021.

A few operators write the output of the left-hand side into a file.

The > command takes the output of a command on the left and writes it as a new file. If the file you specify already exists, it will be overwritten.

If you want to append the new text, rather than overwrite, >> appends to the end of the file. I generally default to >>, because it will create a new file if one doesn’t exist, and I usually don’t mean to overwrite what’s there.

A common reason you might want to do this is to add something to the end of your .gitignore. For example, if you want to add your .env file to your .gitignore, you could do that with echo .env >> .gitignore.11 Another great use is to add a new public key to your .ssh/authorized_keys file.

Sometimes, you want to create empty files or directories. The touch command makes a blank file at the specified file path. If you touch a preexisting file, it updates the time it was last edited without making any changes. This can be useful because some applications use the file timestamp to see if action is needed.

Comprehension questions

- What are the parts of a bash command?

- What is the difference between a relative and an absolute path?

- What are some ways to direct them to run in a particular place on the filesystem?

- How can you copy, move, or delete a file? What about to or from a server?

- Create a mind map of the following terms: operating system, Windows, MacOS, Unix, Linux, Distro, Ubuntu.

- What are the \(3*3\) options for Linux file permissions? How are they indicated in an

ls -lcommand?

Lab: Set up a user

When you use your server’s .pem key, you log in as the root user, but that’s too much power to acquire regularly. Additionally, since your server is probably for multiple people, you will want to create users for them.

In this lab, you’ll create a regular user for yourself and add an SSH key for them so you can directly log in from your personal computer.

Step 1: Create a non-root user

Let’s create a user using the adduser command. This will walk us through prompts to create a new user with a home directory and a password. Feel free to add any information you want – or to leave it blank – when prompted.

I’m going to use the username test-user. If you want to be able to copy/paste commands, I’d advise doing the same. If you were creating users for actual humans, I’d recommend using their names.

Terminal

> adduser test-userWe want this new user to be able to adopt root privileges so let’s add them to the sudo group with:

Terminal

> usermod -aG sudo test-userStep 2: Add an SSH key for your new user

Let’s register an SSH key for the new user by adding the key from the last lab to the server user’s authorized_users file.

First, you must get your public key to the server using scp.

For me, the command looks like this:

Terminal

> scp -i ~/Documents/do4ds-lab/do4ds-lab-key.pem \

~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub \

ubuntu@$SERVER_ADDRESS:/home/ubuntuWe’re copying the public key, but SSH access (argument to -i) is still with the server’s .pem key because there isn’t another one registered yet.

The public key is on the server, but in the ubuntu user’s home directory. You’ll need to do the following:

Create

.ssh/authorized_keysintest-user’s home directory.Copy the contents of the public key you uploaded into the

authorized_keysfile (recall>>).Ensure the

.sshdirectory andauthorized_keysfiles are owned bytest-userwith700permissions on.sshand600onauthorized_keys.

You could do this all as the admin user, but I’d recommend switching to being test-user at some point with the su command.

If you run into trouble assuming sudo with your new user, try exiting SSH and returning. Sometimes, these changes aren’t picked up until you restart the shell.

Once you’ve done all this, you should be able to log in from your personal computer with ssh test-user@$SERVER_ADDRESS.

Now that we’re all set up, you should store the .pem key somewhere safe and never use it to log in again.

The remainder are mostly Windows servers. There are a few rarer OSes you might encounter, like Oracle Solaris. There is a product called Mac Server, but it’s just a program for managing Mac desktops and iOS devices, not a server OS. There are also versions on Linux that run on desktop computers. Despite the best efforts of many hopeful nerds, desktop Linux is pretty much only used by professional computer people.↩︎

Or at least they weren’t supposed to. There’s an interesting history of lawsuits, especially around whether the BSD OS illegally included Unix code.↩︎

Quote from the History of Linux Wikipedia article. Pedants will scream that the original release of Linux was just the operating system kernel, not a full operating system like Unix. Duly noted, now go away.↩︎

RHEL and CentOS are related operating systems, but that relationship has changed a lot in the last few years. The details are somewhat complicated, but most people expect less adoption of CentOS in enterprise settings going forward.↩︎

As of early 2024, Amazon Linux 2 is predominant, but Amazon Linux 2023 (AL2023) is rising in popularity.↩︎

The one exception to this is when you’ve got the same user accessing resources across multiple machines. Then the

uids have to match. If you’re worrying about this kind of thing, it’s probably time to bring in a professional IT/Admin.↩︎Clever eyes may realize that this is just the base-10 representation of a three-digit binary number.↩︎

The root directory at the base of the tree,

/, is its own parent.↩︎It’s worth noting that

scpis now considered “insecure and outdated”. The ways it is insecure are rather obscure and not terribly relevant for most people. But, if you’re moving a lot of data, then you may want something faster. If so, I’d recommend more modern options likesftpandrsync. This isn’t necessary if you’re only occasionallyscp-ing small files to or from your server.↩︎The title of this callout box is also the tagline for the

{magrittr}package.↩︎Note that

echois needed so that the.envgets repeated as a character string. Otherwise.envwould be treated as a command.↩︎