Appendix A — Technical Detail: Auth Technologies

Chapter 16 provided a conceptual understanding of how auth works and what SSO is. I also briefly mentioned a few technologies used to do auth, including LDAP/AD, SAML, and OIDC/OAuth2.0. We’ll get a little deeper into them in this appendix chapter.

Having a basic understanding of these technologies can be helpful when you’re talking to IT/Admins about a data science platform. That said, this topic is beyond the scope of what you need to understand, which is why this is an appendix.

There are two big distinctions between auth technologies. One is between systems that pass tokens to services and, therefore, can do SSO and other systems that provide credentials to the service.1 The other is between modern systems that are designed to work with cloud services and legacy systems that were designed for on-prem software.

| Auth Technology | Token-Based? | “Modern”? |

|---|---|---|

| Service-based | No | No |

| Linux Accounts | No2 | No |

| LDAP/AD | No | No |

| Kerberos | Yes | No |

| SAML | Yes | Yes |

| OAuth | Yes | Yes |

Token-based systems are rising in popularity because they are more convenient for admins and users and are more secure.

One reason token-based systems are more secure is because of credential handling. In a non-token system, the user provides their credentials directly to the service, which passes them along to authenticate. This means you have to trust the service with the credentials. Additionally, if you wanted to use advanced credentials like MFA, biometrics, or passkeys, the service itself would have to implement them. Most services do not, so username and password credentials are the only option.

In contrast, credentials are only ever provided to the trusted identity provider in a token system. That means only the identity provider needs to implement advanced credentials, and less trust in the service is required because it never sees user credentials.

Token systems are also more secure because of how sessions expire. No system requires users to log in every single visit to a service. That’s too demanding. Instead, the system issues a cookie or token that will let the user back in without re-authenticating.

In a credential system, the service itself issues a browser cookie that allows the user back in without re-authenticating until it expires and it’s time to authenticate again. That’s usually a relatively long time, sometimes multiple days.

In a token system, the token to a service has a much shorter life than the time to re-authenticate. When the service encounters an expired token, it checks if the user should have access against the identity provider. This means that changes to authorization propagate as quickly as the short-lived service tokens expire. That drastically limits the risk of a stolen token or someone trying to log back in after they’ve been locked out.

Service-based auth

Many pieces of software come with integrated authentication. When you use those systems, the service stores encrypted username and password pairs in its own database. If you’re administering a single service, this is really simple. You just set up individual users on the service.

But, once you have multiple services, everything has to be managed service-by-service. And the system is only as secure as what the service has implemented. Almost any organization with an IT/Admin group will prefer not to use service-based auth.

System (Linux) accounts

Many pieces of software – especially data science workbenches – can look at the server it’s sitting on and authenticate against the user accounts and groups on the server.

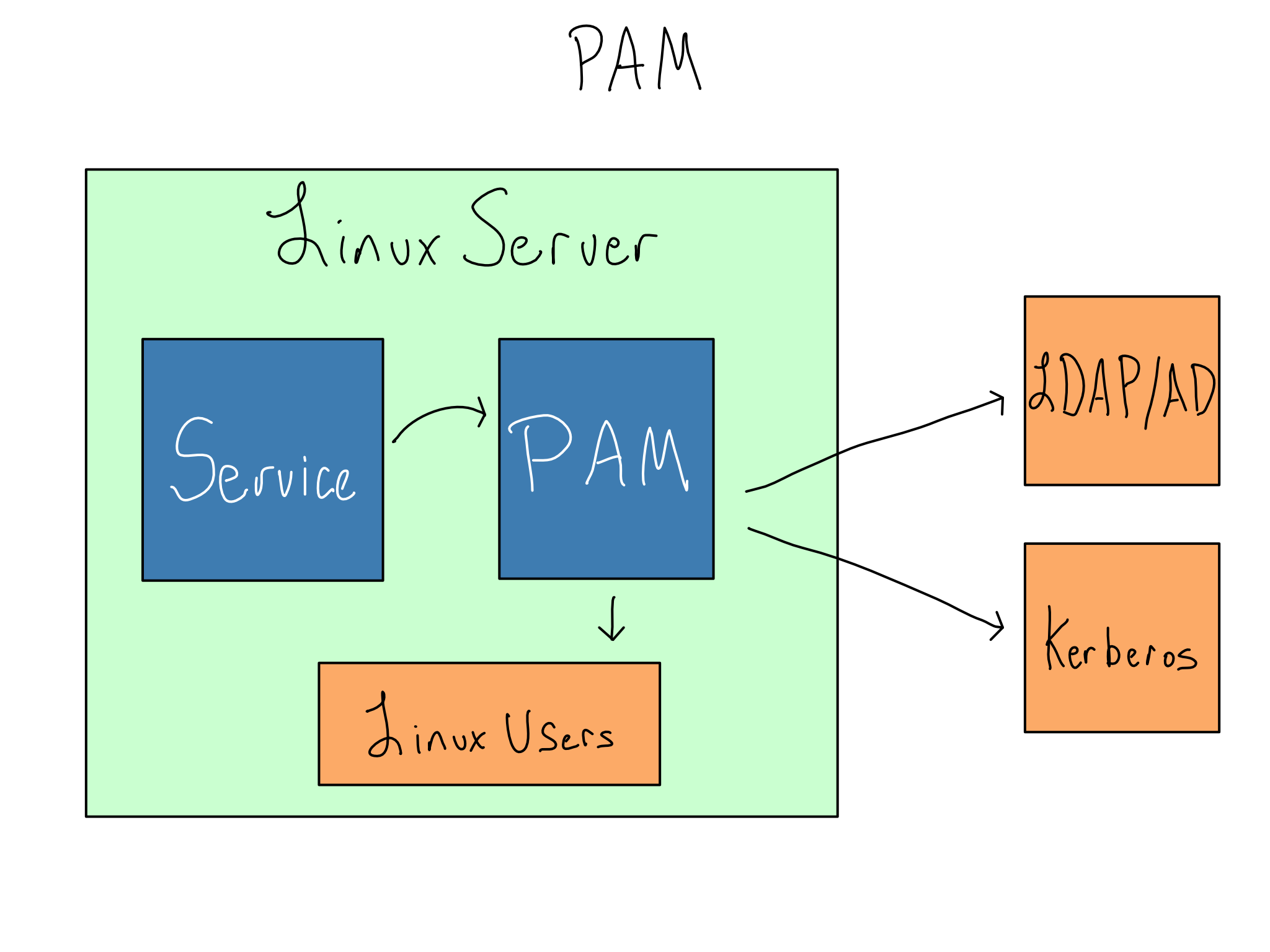

On a Linux server, PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules) allows a service to use the users and groups from the underlying Linux host. As of this writing, PAM is the default authentication method for RStudio Server and JupyterHub.

As the name suggests, PAM includes modules that allow it to authenticate against different systems. The most common is to authenticate against the underlying Linux server, but it can also use LDAP/AD (common) or Kerberos tickets (uncommon).

PAM can also be used to do things when users log in. The most common of these is initializing Kerberos tickets to connect with databases or connecting with shared drives.

When PAM is used in concert with LDAP/AD, the Linux users are usually created automatically on the system using SSSD (System Security Services Daemon). This process is called joining the domain.

Though conceptually simple, the syntax of PAM modules is confusing, and reading, writing, and managing PAM modules is onerous. Additionally, as more services move to the cloud, there isn’t necessarily an underlying Linux host where identities live, and PAM can’t be used at all.

LDAP/AD

For many years, Microsoft’s Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) implementation called Active Directory (AD) was the standard in enterprise auth. It is increasingly being retired in favor of token-based systems like SAML and OAuth2.0.

Some services can use LDAP/AD indirectly via PAM, while others may be directly configured to talk to LDAP/AD.

LDAP is an application-layer protocol, like HTTP. And like HTTP, there is an SSL-secured version called LDAPS. Because LDAP is almost always used only inside a private network, adoption of LDAPS is uneven. The default port for LDAP is \(389\), and for LDAPS it’s \(636\).

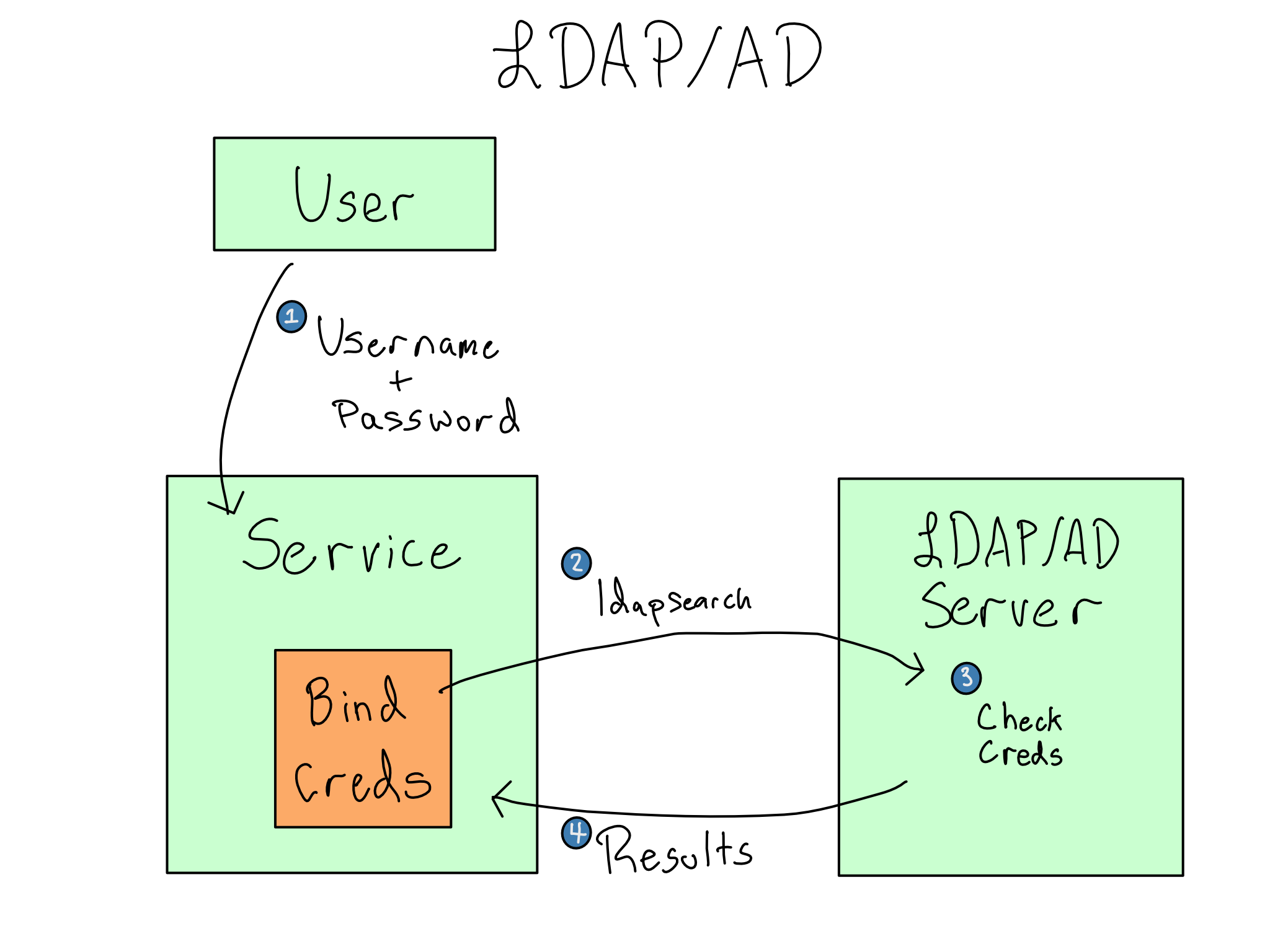

Strictly speaking, LDAP/AD isn’t an authentication tool. It’s a hierarchical tree database that is good for storing organizational entities. Doing authentication with LDAP/AD consists of sending a search for the provided username/password combination to the LDAP/AD database using the ldapsearch command.

When you configure LDAP/AD in an application, you’ll configure a search base, which is the subtree to look for users inside. Additionally, you may configure LDAP/AD with bind credentials of a service account to authenticate to the LDAP/AD server itself.

Standard LDAP/AD usage with bind credentials is called double-bind. Depending on your application and LDAP/AD configuration, it may be possible to skip the bind credentials and look up the user with their own credentials in single-bind mode. Single-bind is inferior to double-bind and shouldn’t be used unless you can’t get bind credentials.

An ldapsearch returns the distinguished name (DN) of the entity that you are looking for – assuming it’s found.

Here’s what my entry in a corporate LDAP directory might look like this:

cn: Alex Gold

mail: alex.gold@example.com

mail: alex.gold@example.org

department: solutions

mobile: 555-555-5555

objectClass: PersonThis is helpful information, but you’ll note that there’s no direct information about authorization. Instead, you configure the service to authorize certain users or groups. This is time-consuming and error-prone, as each service needs to be configured separately.

Kerberos tickets

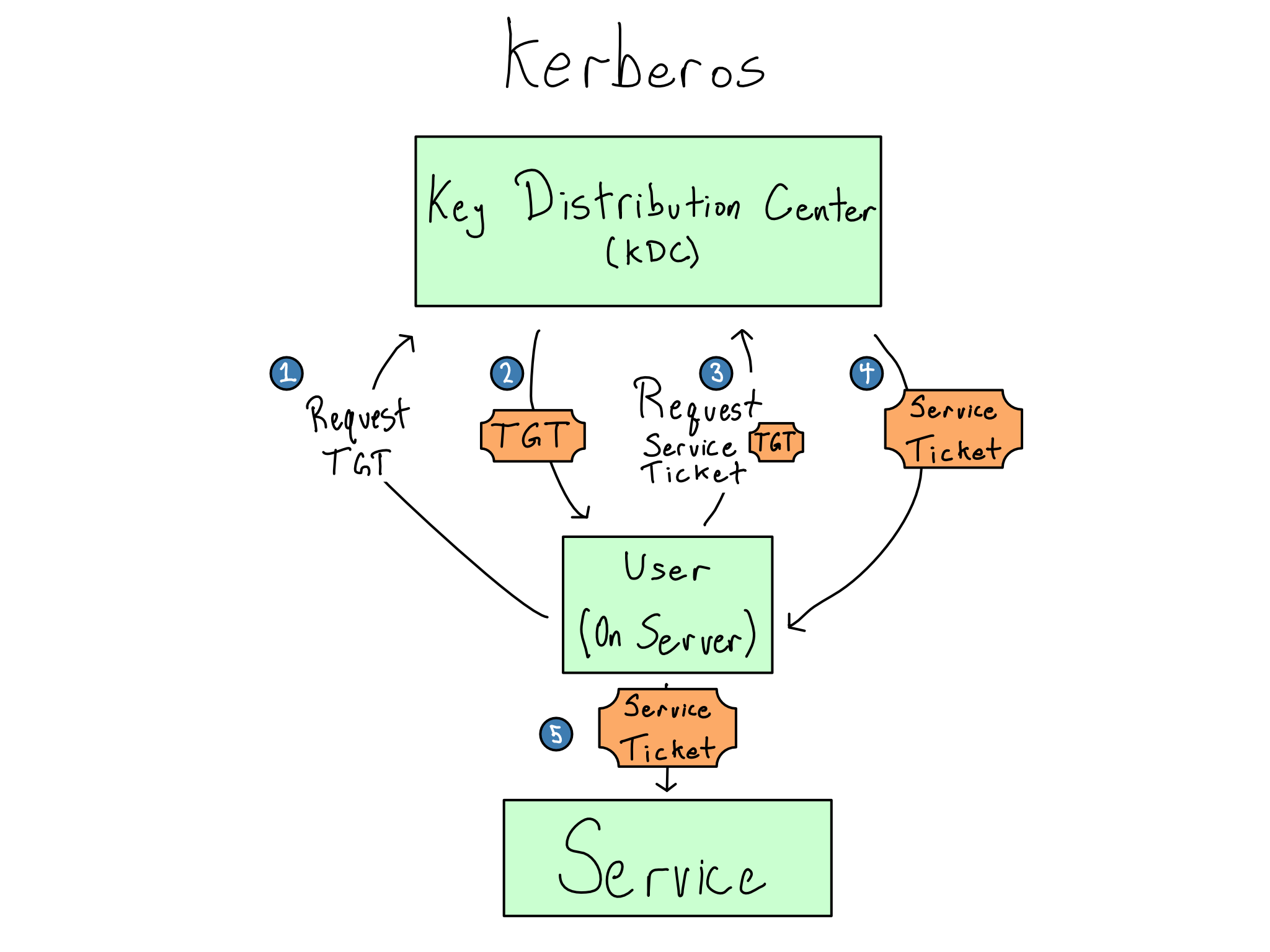

Kerberos is a relatively old, but very secure, token-based auth technology for use inside a private network. In Kerberos, encrypted tokens called Kerberos tickets are passed between the servers in the system. A system that is designed to authenticate against a Kerberos ticket is called kerberized.

Kerberos was widely adopted along with Active Directory, and it’s used almost exclusively in places that are running a lot of Microsoft products. The most frequent use of Kerberos tickets is to establish connections to Microsoft databases.

In a Kerberos-based system, users often store their credentials in a secure keytab, which is a file on disk. They can manually initialize a ticket using the kinit command or via a PAM session that automatically fetches a ticket upon user login.

When a Kerberos session is initialized, the service sends the user’s credentials off to the central Kerberos Domain Controller (KDC) and requests the Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT) from the KDC. Like most token authentication, TGTs have a set expiration period and must be re-acquired when they expire.

When the user wants to access a service, they send the TGT back to the KDC again along with the service they’re trying to access and get a session key (sometimes referred to as a service ticket) that allows access to a particular service.

Kerberos is only used inside a corporate network and is tightly linked to the underlying servers. That makes it very secure. Even if someone stole a Kerberos ticket, it would be very hard for them to use it.

On the other hand, because Kerberos is so tightly tied to servers, it is a difficult fit alongside cloud technologies and services.

Modern systems: OAuth and SAML

Most organizations are now quickly moving toward implementing a modern token-based authentication system through SAML and/or OAuth2.0.

When you log in to a service that uses SAML or OAuth, you are redirected to the SAML/OAuth identity provider to seek a token that will let you in. Assuming all goes well, you’re granted a token and you return to the service to do your work.

Both OAuth and SAML rely on plain HTTP traffic, making them easier to configure than LDAP/AD or Kerberos from a networking standpoint.

SAML

The current SAML 2.0 standard was finalized in 2005, roughly coinciding with the beginning of the web’s modern era, with Facebook launching just the prior year.

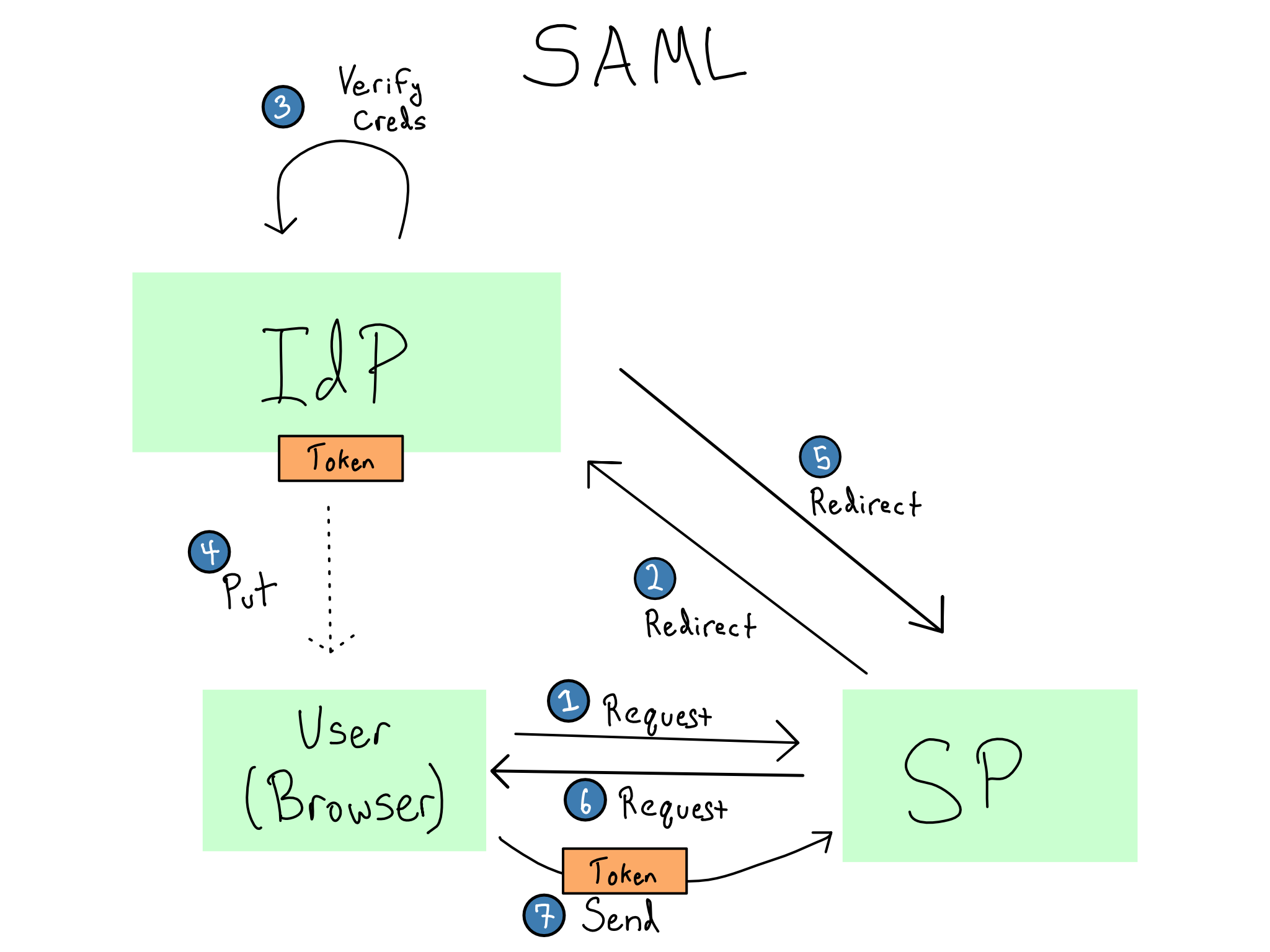

SAML was invented to be a successor to enterprise auth methods like LDAP/AD and Kerberos. SAML uses encrypted and cryptographically signed XML tokens that are generated through a browser redirect flow.

In SAML, the service you’re accessing is called the service provider (SP) and the entity issuing the token is the SAML identity provider (IdP). Most SAML tooling allows you start at either the IdP or the SP.

If you start at the SP, you’ll get re-directed to the IdP. The IdP will verify your credentials. If the credentials are valid, the IdP will put a SAML token in your browser, which the SP will use to authenticate you.3

A SAML token contains several claims, which usually include a username and may include groups or other attributes. Whoever controls the IdP can configure what claims appear on the token at the IdP. The SAML standard itself is for authentication, not authorization, but it’s very common for an application to have required or optional claims that it can interpret to do authorization.

OAuth

OAuth was started in 2006 and the current 2.0 standard was finalized in 2013. OAuth 2.1 is under development as of 2023.

OAuth was designed to be used with different services across the web from the beginning. Any time you’ve used a Log in with Google/Facebook/Twitter/GitHub flow – that’s OAuth.

OAuth relies on passing around cryptographically signed JSON Web Tokens (JWTs). This makes OAuth more straightforward to debug than SAML because the JWT is plaintext JSON with a signature that proves it’s valid.

Unlike a SAML token that always lives in a browser cache, JWTs can go anywhere. They can live in the browser cache, but they also can pass from one server to another to do authorization or can be saved in a user’s home directory. For example, if you’ve accessed or another Google service from R or Python, you may have manually handled the resulting OAuth token in your home directory.

OAuth is an authorization scheme, so the contents of a JWT are about the permissions of the bearer of the token. A related standard called OpenID Connect (OIDC) can be used to do authentication with OAuth tokens. Over the next few years, I fully expect all data access to move toward using OAuth tokens.

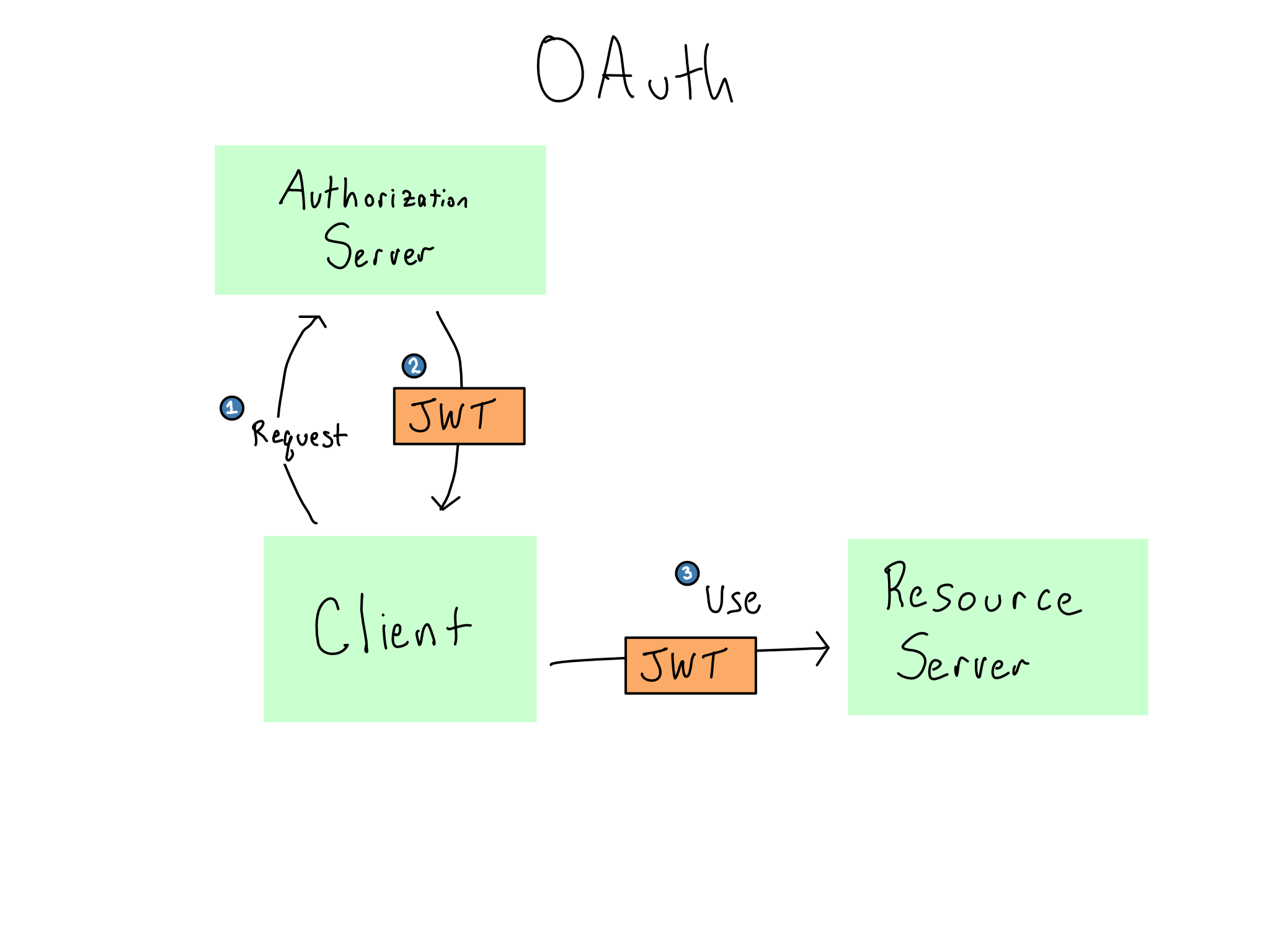

In OAuth, the service you’re trying to visit is called the resource server and the token issuer is the authorization server. When you try to access a service, the service knows to look for a JWT that includes specific claims against a set of scopes. If you don’t have a JWT, you must seek it from the authorization server.

For example, if you want to read my Google Calendar, you need a JWT that includes a claim granting read access against the scope of events on Alex’s calendar.

Unlike in SAML where action occurs via browser redirects, OAuth makes no assumptions about how this flow happens. The process of requesting and getting a token can happen in several different ways, including browser redirects and caches, but could be done entirely in R or Python.

User provisioning

When you’re using a service, users often need to be created (provisioned) in that system. Sometimes, the users will be provisioned the first time they log in. In other cases, you may want the ability to provision them beforehand.

LDAP/AD is very good for user provisioning. You can often configure your application to provision everyone who comes back from a particular ldapsearch. In contrast, token-based systems don’t know anything about you until you show up for the first time with a valid token.

There is a SAML-based provisioning system called SCIM (System for Cross-Domain Identity Management) that is slowly being adopted by many IdPs and SPs.

As in Chapter 16, I’m using the term token as a summary, but Kerberos, SAML, and OAuth all have different names – more on that below.↩︎

To be precise, possible if integrated with Kerberos, but unlikely.↩︎

The diagram assumes you don’t already have a token in your browser. If the user has a token already, steps 2–5 get skipped.↩︎